Author: Sam Kuschke

Date: August 30, 2022

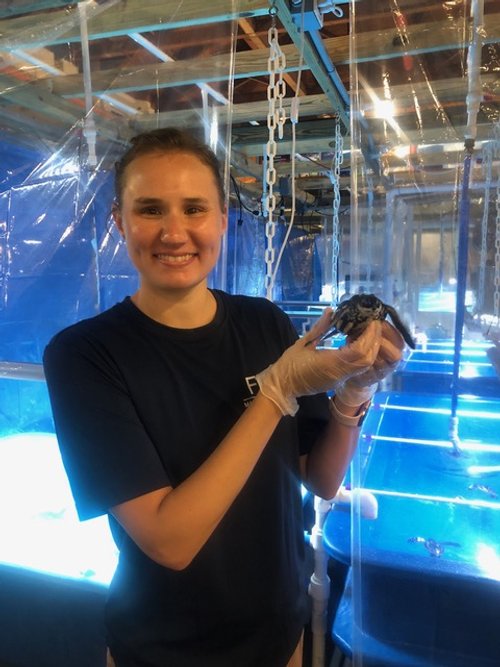

Dr. Sam Kuschke wears many hats - a licensed veterinarian, a Ph.D. student at the University of Tennessee, and a graduate research assistant at the FAU Marine Lab (just to name a few). The following story was written by Dr. Sam for our collaborators at Upwell outlining her work with leatherback hatchlings here at the FAU Marine Lab. See the full article on Upwell’s website here .

The leatherback is the largest of all sea turtle species, and because of their highly migratory nature and unique lifestyle characteristics, our ability to study them has been limited. Now is the time to act if we are going to save the highly endangered Eastern Pacific population of leatherbacks, but something is holding us back. There are huge gaps in our baseline knowledge of this species. In addition, we also don’t fully understand the effect that climate change is having on sea turtles.

Our team at the FAU Marine Lab works with the staff at the Gumbo Limbo Nature Center and Loggerhead Marinelife Center to collect a sample of leatherback hatchlings as they emerge from their nests on beaches in Boca Raton and Juno Beach, Florida. A small subset of turtles remains at the FAU Marine Lab for additional research and are cared for by me and the rest of the leatherback team. As a graduate research assistant and veterinarian, I am a part of the daily care team for our turtles. This collaboration has led to the development of groundbreaking husbandry and care techniques necessary to support leatherback sea turtle hatchlings.

For my own Ph.D. work I am investigating the bacteria that live on the skin of leatherback sea turtle hatchlings, blood values in leatherback sea turtle hatchlings, and the effect that climate change has on both. I collect samples from each turtle on the day they emerge from their nests and then again in 3 to 4 weeks. In the preliminary analysis of my bloodwork samples from hatchlings, I found some alarming trends! Turtles emerging from hotter nests are suffering from dehydration, inflammation, and possibly infections; they also have decreases in important protective blood proteins. Essentially, hatchlings coming out of hotter nests are suffering from a lot of physiologic stress.

To understand the importance of my findings it’s important to think about what it is like to be a sea turtle hatchling on the day they hatch. Tiny sea turtle hatchlings must dig up out of the sand from about 27 inches deep. That is over two feet of sand for a tiny turtle! Then they have to crawl their way down the beach, which can be incredibly far. Next, the leatherback hatchlings go out into the ocean, swimming continuously, without sleeping, to their offshore nursery sites about 12 miles offshore and enter the Gulf Stream. They do all of this while also trying to avoid predators and any man-made hazards that pose a threat. Essentially, being a hatchling is REALLY HARD! Piling on additional physiologic stress such as dehydration or inflammation is likely to negatively impact their overall fitness and survival. This is probably especially true during a hatchling’s very challenging first few days of life and is likely to decrease their already low survival rates.

To combat these challenges effectively we still need more information, and my team of collaborators is working towards this, but spreading the word that climate change is impacting hatchlings before they even emerge is a start! With support from Upwell, I was fortunate enough to be able to present this information at two conferences this summer, the Wildlife Disease Association (WDA) conference and the first Global Amphibian and Reptile Disease (GARD) conference. Sharing my findings is essential because we still need to integrate the information to fully understand the parts of this problem and the other challenges that leatherback hatchlings are facing.

Climate change impacts are widespread and it is only with collaboration across multiple entities that we will start to find answers and solutions. My research is a perfect example of what can be gained when different groups work together towards our common goal of understanding threats to leatherbacks and how to protect them in our changing world.