Author: Hannah Mauer

Date: 2/17/2025

Happy belated Valentine’s Day from all the members of the FAU Marine Lab!

The month of February has been very busy for the SEA Scholars with many outreach events (and many more to come)! What better way to honor Valentine’s Day than to celebrate the marine life we love so much? We decided to spread the love by creating our own marine-themed and scientifically accurate valentines to share with our community. There is nothing we SEA Scholars enjoy more than communicating the research done at the FAU Marine Lab with a good science pun. Even though Valentine’s Day passed, we still wanted to share their sweet notes – and the science behind them, of course – with you!

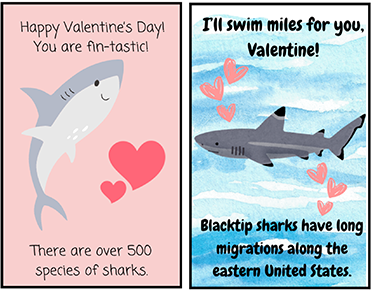

You might only have one true valentine, but there are over 500 species of sharks to love! One of the most common sharks to spot during a south Florida winter and early spring is the blacktip. Blacktip sharks migrate south along the east coast of the United States each year in search of warmth and food. At the FAU Marine Lab, we monitor their migration via airplane, flying from Miami to Jupiter and counting how many are within 200 meters of the shore. They begin to move northward again as those waters warm, following schools of fish and heading towards their mating and breeding grounds in Georgia and the Carolinas… talk about a long-distance relationship!

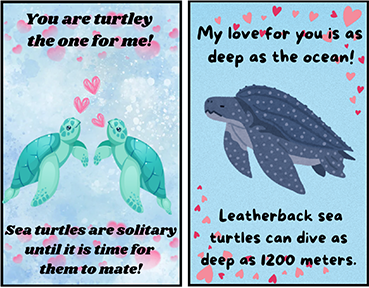

Sea turtles aren’t buying last-minute chocolates and teddy bears, but they are also traveling hundreds to thousands of miles to mate and nest in Florida! Both male and female sea turtles are solitary creatures until they migrate back to nesting beaches to mate. Once they migrate, love is in the water around the same time as our own sweetheart season, with March 1st marking the onset of sea turtle nesting. Each year, leatherback sea turtles are the first to nest in Florida with a handful of early birds often laying nests in February. In fact, the second nest of the season in Florida was laid on Valentine’s Day this year! Although leatherbacks arrive first to nest, loggerhead and green sea turtles also nest in southeast Florida in much higher numbers.

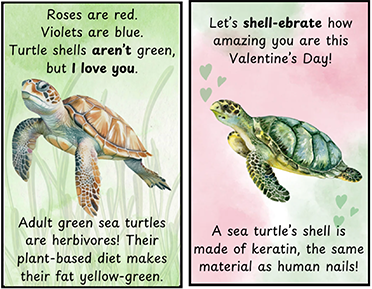

When Juliet pondered, “What’s in a name?” was she referring to her tragically star-crossed valentine or these south Florida’s nesting sea turtle species? She was definitely talking about Romeo…but it turns out the common names of these sea turtles can tell us a bit about them! Leatherbacks get their name from their uniquely pliable and leathery shell that allows them to dive to great depths (over 1200 meters!) to eat gelatinous prey like jellyfish and salps. In contrast, the hard shells of loggerhead and green sea turtles are made of keratin, the same material that makes up our own nails and hair. Loggerhead sea turtles get their name from their large heads with powerful jaws that help them crunch through conch shells, crabs, and lobsters. The green turtles’ name gives you a hint as well about their diet. Green sea turtles, which as adults are herbivores, get their name from eating algae and seagrasses. That diet turns their fat (but not their shells!) a yellowish-green color.

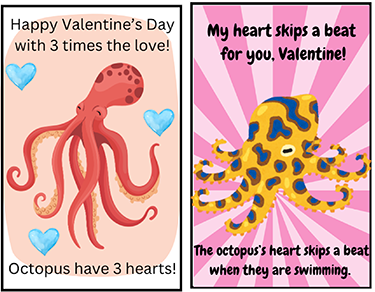

Octopus have lots of love to give with their three hearts. Those three hearts are located in the octopus’s mantle, the sac behind its head. Two brachial or gill hearts direct blood flow to the gills to become oxygenated. That oxygenated blood is then circulated to the rest of the body by the systemic or main heart. Octopus blood is quite thick due to the copper-based protein (hemocyanin) in their blood that binds with oxygen. (We have the iron-based protein called hemoglobin that serves the same function). Their blood is blue instead of red when it binds with oxygen! With this blue blood, the octopus’s heart rate and blood pressure increase when they become increasingly active, but hemocyanin is less efficient at transporting oxygen than hemoglobin, which makes it difficult to keep up with the oxygen demand needed for such activity. So, octopus tend to move slowly or crawl along the seafloor to avoid an oxygen debt. Also, when an octopus swims or uses jet propulsion, its mantle is under such great pressure that its veins are incapable of returning blood and the hearts skip a beat. That’s why octopus often just swim in short bursts. Their hearts may also skip a beat when they are startled, just like our human heart can palpitate when we are stressed, anxious, or in love.

You know who doesn’t get enough love? Plants! With so many charismatic megafauna in our oceans, arguably equally impressive, but less flashy plants, like seagrass, often go unnoticed. However, without seagrass, marine animals like sea turtles and sharks would be without a food source – yes, some sharks, like bonnetheads, are omnivores and feed on both plants and animals! Seagrass also provides a habitat for more of our favorite critters like octopus and queen conchs. Seagrass not only helps our favorite marine animals survive, but us as well! Seagrass is a true plant with stems, roots, leaves, and flowers. Just like other plants, they convert carbon dioxide and sunlight into sugar via photosynthesis, releasing oxygen for us (and marine animals) to breathe. We can think of seagrass as the lungs of the ocean, and it deserves love too!

To the subscribers of our newsletter, visitors of the gallery, and members of the public who we meet at outreach events, you are shrimp-ly the best! If you are interested in downloading our free valentines head to our website and share them with your friends, family, and loved ones!