Author: Sam Trail

Date: August 20, 2025

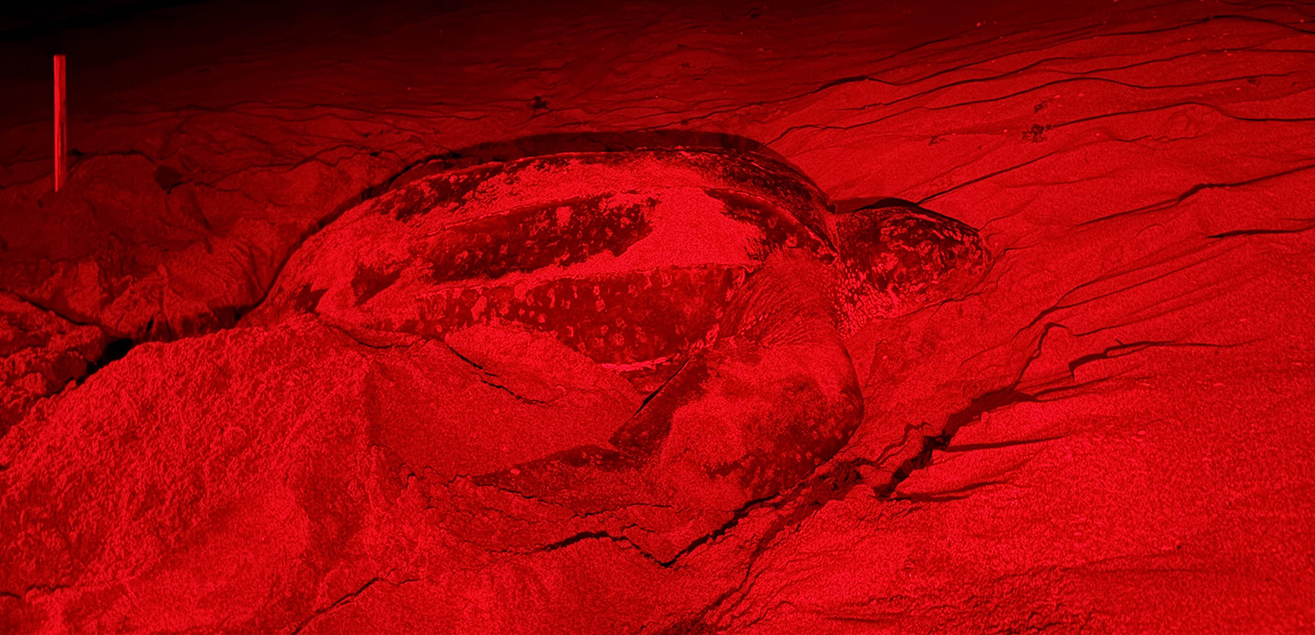

This has been a record-breaking year for leatherback nesting in the state of Florida; as of July 31st, 1,996 nests were deposited! Each morning, crews of sea turtle experts survey designated beaches all over the state and identify leatherback nests based on species-specific tracks in the sand. Less commonly, some scientists patrol beaches at night and, under the glow of red turtle-friendly lighting, spot actively-nesting, mature females. That procedure enables them to answer questions that tracks in the sand, alone, can’t explain.

At the Florida Atlantic Marine Science Lab, two graduate students (Schelli Linz and Elizabeth Schultheis) hold positions as night-time field technicians at the Loggerhead Marinelife Center (LMC) in Juno Beach, Florida. Schelli is a Ph.D. candidate in Dr. Sarah Milton’s lab, and Elizabeth is a Master’s student in Dr. Jeanette Wyneken’s lab. Their positions allow them to monitor and encounter nesting females at Juno and Jupiter beaches between April and June. During those months, Schelli and Elizabeth are obviously nocturnally active as they systematically patrol LMC’s 9.5-mile stretch of beach on ATVs each night between 9 pm and 3 am, in a search for nesting turtles.

They’ve each been asked how they adjust to a nocturnal schedule, while simultaneously fulfilling their usual day-time responsibilities as full-time graduate students. Schelli responded “As best I can,” explaining that she often stays awake until 3 am even on her days off, just to maintain some semblance of a normal circadian rhythm. Elizabeth admits “Honestly, I don’t think I ever did!” She instead sneaks in a nap before her shift. Otherwise, she remains a sleep-deprived student that hasn’t much changed her sleep schedule.

Upon encountering a nesting female, researchers like Schelli and Elizabeth collect valuable information about the female that would otherwise remain unknown if only tracks were observed. For example, she may be individually identified by external hindfoot tags or from an injected Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tag – the same technology used to microchip your pet. Identifiers like these tags enable researchers to determine if she has nested on their beach before and if so, when (the year) and how frequently (that season). Alternatively, the absence of these tags indicates that turtle is a “neophyte”, that is, new to our beach and might also be a first-time nester. This information provides important context for collecting other kinds of data such as measurements of body size and condition (are there injuries?), as well as biological samples of blood or skin (which can be used to obtain a plethora of information, from diet to genetics). That identification and associated information are even more valuable when during the same season, this turtle is encountered several times. Elizabeth explains, “We might encounter them three, four, five or more times…those turtles that are ‘loyal’, we’ll get a lot of information throughout their nesting period.”

|

Ph.D. Candidate Schelli Linz measures the carapace of a nesting leatherback. |

LMC's research department began a saturation tagging program for nesting leatherbacks in 2001, that program is now run by Vice President of Research (and Florida Atlantic Marine Lab alum), Dr. Justin Perrault. The goal was to identify the entire leatherback population nesting on Jupiter and Juno beaches. This 20+ year comprehensive sampling effort is achievable, but is time- and labor-intensive. The 'Goldilocks’ size of this nesting population appears to be just right – not too big, not too small – and often shows site fidelity to this ‘hot spot’ nesting beach in southeast Florida. LMC’s beach surveys often document around 200 leatherback nests per year. Elizabeth points out, “the Northwest Atlantic leatherback population (to which these turtles belong) is slightly increasing or stable, but it doesn’t compare to the number of nesting loggerhead and green turtles we see every year.” There are not so many individual leatherbacks in the population that it would be impossible to tag all the nesting females (as is likely the case for loggerheads and greens in this area, with thousands of nests recorded per year on the 9.5-mile stretch of beach). Importantly, there aren’t so few nesting females that the nightly efforts feel futile. Schelli equates this leatherback nesting population to her time growing up in Catholic school:

“The leatherbacks on this beach are kind of like going to Catholic school – you know every single person in your school. Whereas going to public school, you might know of a lot of people, but you don’t know everyone. There are way too many people.”

On average, Schelli and Elizabeth may encounter 2-3 leatherbacks per night; occasionally, they get skunked, seeing nothing but the waves and other species on their ride. Although that doesn’t seem like many, searching for leatherbacks on the beach is much easier than searching for them in the water. At sea, finding leatherbacks is much like searching for a needle in a haystack.

Leatherbacks are of particular interest to these researchers because when it comes to extant sea turtles, they are often the exception to any biological or behavioral ‘rule.’ As Schelli jokes, “if all the other marine turtles do something, the leatherbacks are like ‘mmm that’s not for me, I’m going to be different.’” This stems from the fact that they are from a different taxonomic group (family Dermochelyidae) than all the hard-shelled sea turtles (family Cheloniidae). They are also highly specialized, open-sea predators that feed exclusively on jellyfish, salps, and other “gelatinous zooplankton” that are found in open water.

While helping LMC with their continued saturated tagging efforts, both Schelli and Elizabeth are attempting to answer their own research questions. Schelli is focused on identifying molecular biomarkers of toxin (a natural, yet harmful substance, such as those released from harmful algal blooms) and toxicant (a synthetic, harmful substance such as pesticides and heavy metals) exposure in nesting leatherbacks. Night work provides her with the perfect opportunity to collect blood and skin samples that can be used to test for these substances. She is also determining which biomarker tests are most useful in identifying exposure to these harmful substances and the impacts of that exposure. Her analyses will help future efforts to monitor leatherback exposures by simplifying the whole process and reducing their cost.

Elizabeth is determining whether a harmful fungi (Fusarium spp.) is present in leatherback nests and if it is, how much is there. “These fungi are believed to cause sea turtle egg fusariosis, which is known to decrease hatching success and increase egg mortality.” By working at night, Elizabeth is able to collect sand samples from the egg chambers dug by the female just before she releases her eggs, and then again just after the eggs hatch and the hatchlings depart. Comparisons between those samples enable her to look for environmental correlations that might influence changes in the abundance of these fungi during the incubation period. She also uses her unique encounters with nesting females to swab a sample of the eggs as they are released, but before they reach the sand. Those swabs enable her to determine if the fungi originate from the mother or the sand environment.

|

Master’s student Elizabeth Schultheis collects a small sample of sand from the egg chamber of a nesting leatherback. |

Leatherback nests are still hatching in some areas, but it’s a wrap on encountering leatherback females this season. Thinking back on the 2025 nesting season, Schelli and Elizabeth described their favorite part of leatherback night work. Schelli reflects, “although it is a lot of manpower and exhausting nights, it’s a unique and very valuable opportunity to work with these animals.” Elizabeth gleefully describes that “every night is different…sometimes it’s not until 3 in the morning at our last pass, when we are all ready to go home, that we encountered a turtle. Then we all have to gear up and say, ‘Let’s go!’ It’s still so exciting.” These two energetic scholars have several months to catch up on sleep and to analyze their samples before another year passes, and the leatherbacks come back to once again nest on our beaches!

The described and pictured research was conducted under Florida Marine Turtle Permits: MTP25-285, MTP25-053A, and MTP25-205 and approved by the Florida Atlantic University IACUC.

|

|