Photo credit: Jim Abernethy

Author: Sam Trail

Date: December 12, 2024

Where do tiny turtles go once they leave our beaches? Each year, the FAU Marine Lab and the nonprofit organization Upwell continue our highly productive collaboration to answer this key question by releasing small, juvenile turtles, reared at the FAU Marine Lab for 2-4 months, with micro-satellite tags attached to their shell. During their period in captivity, the turtles grow to approximately 120 g. At this weight, turtles are about the size of your palm.

These turtles are released in the Atlantic Ocean’s Gulf Stream Current, the location where they would normally be found at this stage of their development. The information gained from these studies helps our researchers answer vital questions about where they go and how an open-ocean environment impacts their subsequent development.

In the Lab

During those few months of captive rearing, the many hands of the FAU Marine Lab work tirelessly to ensure the turtles remain healthy. We monitor how much each turtle eats, grows, and even poops– what goes in must come out! Although the Marine Lab conditions may appear quite artificial from the bird’s-eye view of our visitors’ gallery, our captive rearing practices actually mimic key aspects of the natural environment for turtles of this size. For example, loggerhead and green hatchlings are housed in floating baskets, pictured below, to mimic the nooks and crannies they seek out in the floating mats of an alga, known as Sargassum. These algal mats provide young turtles with hiding places from predators as they grow, and a microhabitat in which they can feed opportunistically on invertebrates living in the floating mats. While in the Marine Lab, our students also function as “cleaner fish” providing the growing turtles with a light sponge bath once weekly to mimic that natural symbiotic relationship.

And, if you notice those bright, colorful dots on the turtles’ shells, those are our turtle “name tags” painted on with non-toxic children’s nail polish, so we can identify who is who if any turtles decide they want to hop out of those baskets to go for a swim or nab food that has fallen to the bottom of the tank.

In the Ocean

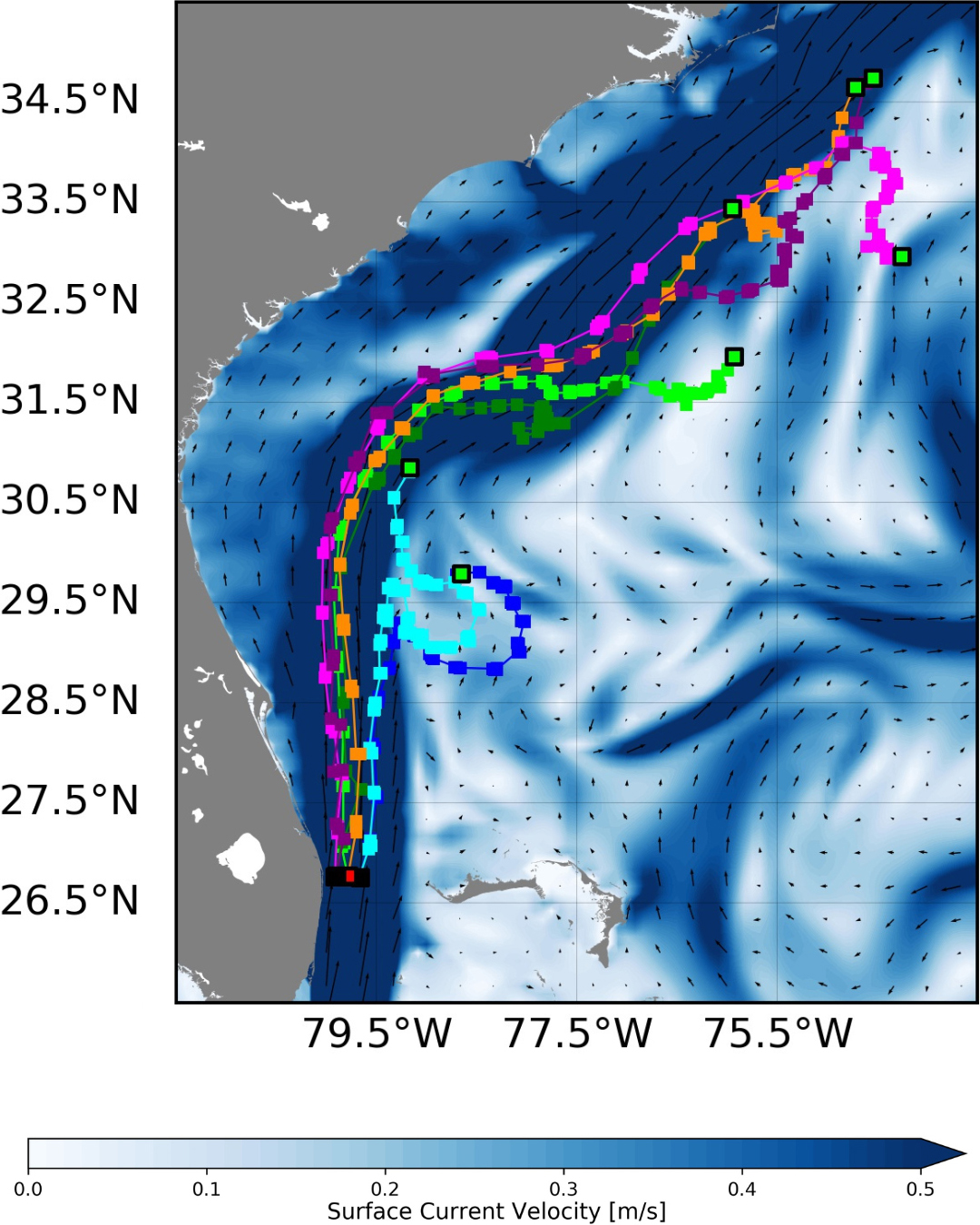

These turtles, quite literally, “grow up so fast,” so after their brief time in the FAU Marine Lab, they get a boat ride several miles offshore where they are released in the Gulf Stream Current by our wonderful Turtle Transport Team (pictured below). This season, eight juvenile loggerhead turtles with micro-satellite tags were released in different parts of the Gulf Stream. Since then, we have been monitoring their movements based upon the data from those tags. Looking at the map below, the darker blue indicates faster moving surface water currents of the Gulf Stream. Each colored line is the track of a different tagged loggerhead turtle! You can see most of the turtles are using that current as a conveyor belt that displaces them northward. However, some turtles make detours into the circular eddies that form to the east of the Gulf Stream current. These data sets contribute to our understanding of how juvenile turtles move about and what they do during the initial stages of their migration within the North Atlantic Ocean.

Photo credit: Jim Abernethy |

photo credit: Upwell/Tony Candella |

|

Dive Comparisons

In addition to providing information on their location, the tags have pressure sensors that record what happens when these turtles perform dives. Juvenile loggerheads, for example, spend more than half of each day diving, mostly at depths no greater than 18 feet below the ocean surface. However, occasionally their dives are as deep as 30 feet, which is about the height of a three-story building! This may seem pretty deep for a small turtle, but leatherback turtles of similar size and age routinely make much deeper dives. While both species seem to use the current to travel, tagged leatherbacks of the same age class make dives down to more than 120 feet in depth, which is closer to the size of a 13-story building! This discovery coincides with what we know about their behavior as adults. Leatherbacks are deep-diving specialists equipped with a compressible carapace that allows the turtles to withstand the pressures associated with achieving those depths. Hard-shelled loggerheads cannot tolerate those conditions, and so, never dive that deeply.

Thanks to these tiny turtles, the FAU Marine Lab and Upwell are untangling big mysteries about the at-sea behavior of very young sea turtles!

Photo credit: Jim Abernethy |